我的中国名字叫尤丽。我是瑞士苏黎世人。但我常常开玩笑地说,我不是老外,我是老杭州。

这里的小巷子什么的我特别熟悉,我走路,我骑自行车,我特别爱这种比较悠闲,或者说有一种怀旧感的状态。

我生活、做研究也是一样的。

其实人已经发生了很大的变化,但生活没有发生太大的变化。我就感觉像康德那样的,他也一直没有离开他的小镇,但他也想着很大的事情。

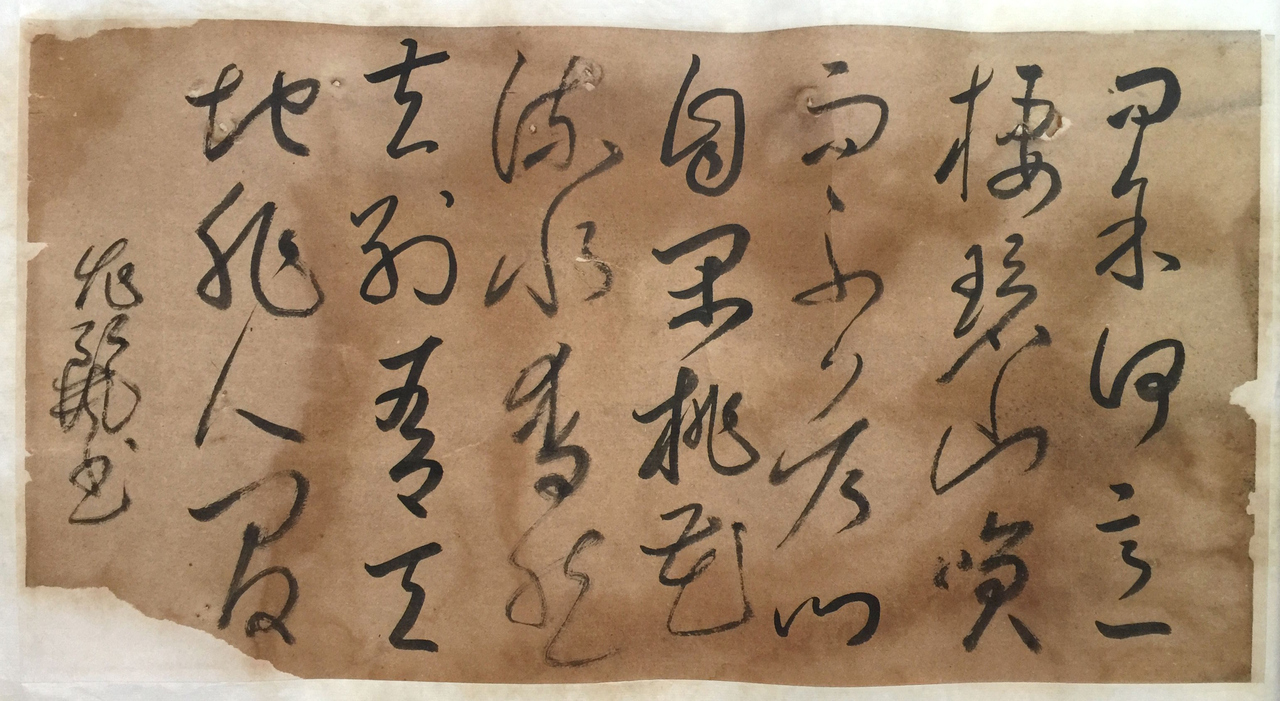

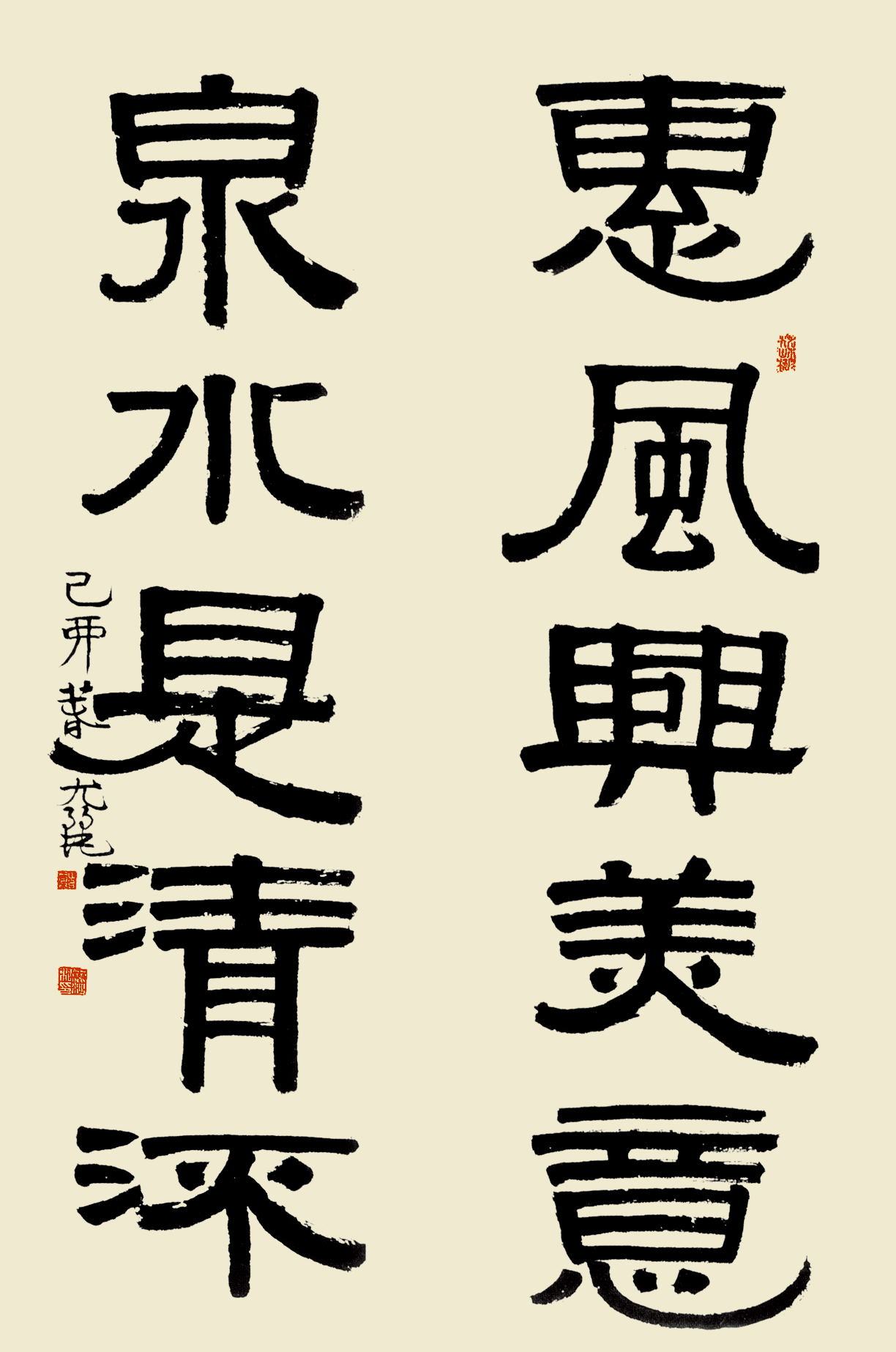

书法好像是音乐中的一种乐谱,或是舞蹈里的一种动作,一直觉得这很美。

每个帖像不同的舞蹈家一样,它用不同的身体语言去创建一些不同的痕迹。

第一堂书法课,我哭了

在苏黎世大学读东亚美术史专业第三年,我获得了奖学金。1993年8月底,来到中国美术学院念书。记得是在老城站下的火车,坐上三轮车,经过河坊街,来到湖旁的校园,一切都这么美好。

在苏黎世大学一位日本老师的书法课上,我第一次临摹《兰亭序》,喜欢上了磨墨、用毛笔写汉字。不过在中国美院,留学生不能同时读两个专业,必须作出选择。一位法国同学和我说,不要学理论,要学实践,于是我就选择了书法专业,走上了书法生之路。第一堂书法课,李文采老师抽着烟,坐在那里等着给我们上课。我来到教室有点迟,只有第一排还有空位。老师一口宁波话,一口接一口抽烟,在黑板上写一笔行草书,我听不懂看不懂,哭了想回家。

不料,这一读,一年变十年,一读读到了硕士毕业。

在书法里找到爱情

当时学习中国传统艺术的留学生,大部分拥有或想要拥有艺术家的身份。我既不是艺术家,又不是什么理论家,说得好听一点,就是所谓的白纸,逐渐地在书法学习中找到归属感。

上世纪90年代还是非手机时代,南山路很幽静,偶尔开过去几辆枣红的桑塔纳或夏利。早晨我背一把剑,骑着28英寸的永久牌自行车,到六公园打拳练剑,上午上专业课,下午、晚上在教室写字,写到熄灯,日复一日,非常专注。认识那时还在读本科的鲁大东之后,书法不仅是事业,是信仰,更是爱情。

读本科的时候,我的班主任对我说,因为我小时候没用过筷子,所以写不好字,所以我不算是一个听话的学生。二年级的时候,我课外坚持临摹了一年的颜体,老师有点崩溃。三年级的时候,我向王冬龄老师借了《张迁碑》的拓片,三天里把自己锁在寝室里,按原大通临了最喜爱的碑文。

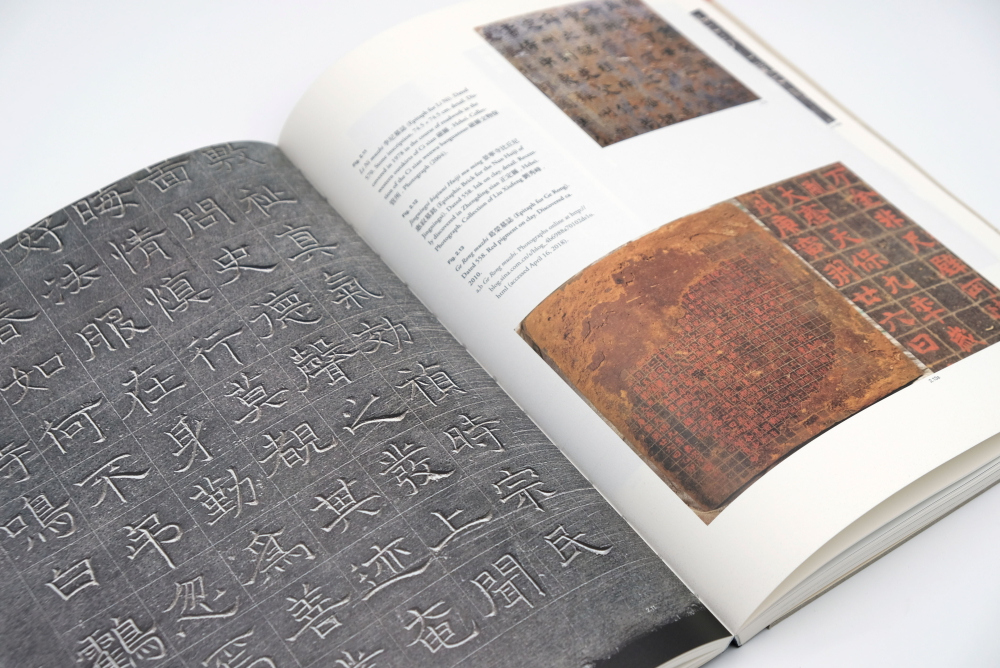

那时一些老师的看法,我不理解。比如有老师说,我们不用去参观西安碑林,看印在书上的拓片就好了。石刻是石头,拓片是一张纸,字帖是一本书,虽然都再现同样的书法,但是怎么会说它们是一样的东西呢?

那时候我做过一个实验:我在校园里捡了一块砖,刻上“佛慧”两个字,拓印,把拓片缩小复印,跟山东摩崖刻经大字拓片的印刷品作比较,发现视觉上没有多少差别。这个实验,奠定了我研究石刻的出发点——研究学习石刻铭文必须考察原石。

我书中的核心人物,是北齐的书僧僧安道壹。我和他是在1996年结的缘。本科、硕士毕业论文都写了与他有关的课题。我与我先生鲁大东在多次实地考察中追随着他的足迹。我负责拍摄,鲁大东负责做笔记画图。硕士论文就基于这些第一手资料。虽然硕士论文获得了老师的好评,但是朱关田先生的评语说,这是一篇书法论文,又是一篇考古报告,让我反省:如果一篇论文仅仅是资料性的,不含有新的观念,是不够的,而我的研究没有明确的个人观点。

2004年春天,苏黎世大学承认我的中国硕士学位,于是我开始读博士。那时不用修学分,不用参加讨论课,这就意味着没有学习框架,全部要靠自己,学习很难有进展。中间我还生了个宝宝,她还在我身体里的时候就陪着我们考察,在参加各种研讨会中长大。2012年,导师Helmut Brinker不幸突然过世了,我要全世界范围重新找导师,最后美国哥伦比亚大学的韩文彬老师接手指导了我。他看了我的提纲、目录说:“这些内容可以写三本书。你先把第一本写好,三个章节就可以了。”

课题就回归于北齐,回归于僧安道壹。韩老师再让我用三句话概括我的论文:内容概括、新的观点、与别的研究不同的地方。三句话,我写了整整一个月!思路清楚之后,老师又明确地在时间上给了压力,写作就顺利多了。最后我花了一个寒假的时间,整理了几百个图版,鲁大东一张一张地制图。2015年3月,我在苏黎世大学顺利通过毕业答辩。不过,根据苏黎世大学的要求,要拿到博士学位,需要正式出版论文。回到杭州,幸运的是我的论文获得了高士明院长的重视,他承诺视觉中国研究院将会出版这本书。

我的“二胎”诞生了

论文是论文,书是书,从某个角度来看,把论文升级到出版物,相当于重写一遍。写作是种神奇的事情,这四年当中,论文不仅经历了几次大修改,而且也过了种种难关,比如解决图版版权的问题。

我属金牛座,也许有人觉得我过于严肃,甚至乏味无趣,但是我能坚持到底。可能是我的执着感染了许多人,大家都愿意为这本书的问世付出力量。这里特别要感谢的是视觉中国研究院的高士明、王良贵和周净,英文编辑美国的Anne Mc Gannon,聿书堂的张弥迪和陶俊霞,浙江人民美术出版的王雄伟和罗士通诸位先生、女士。

今年年初,在海虹印刷厂,听着印刷机的声音,我觉得这是最美妙的音乐,你们信不信?

好事多磨,3月底,我终于把近30多公斤的书扛到苏黎世,把规定数量的书交给大学,终于顺利地把博士学位拿到手。

为了能够把我的研究成果跟更多的读者分享,接下来的计划主要是出中文版。中文版的排版设计会有些不同,有文内图,不再是两册的豪华版。

为这项研究,我的先生鲁大东买了很多拓片和书籍,积累成一个有专题的收藏,策划以这本书为主题的展览,包括我在中国美院读书时的作品资料,去展示一个对中国书法满怀热爱和敬畏的外国人的学习经历,这也许是一个有意义的事情。

写于2019年6月

尤丽(Elisabeth A. Jung Lu),现居中国杭州,学者,书法家,苏黎世大学博士。曾于中国美术学院书法与篆刻艺术专业就学十年,2002 年获硕士学位。2015年,在苏黎世大学完成博士论文。论文导师为苏黎世大学Hans Bjarne Thomsen 和哥伦比亚大学的韩文彬(Robert E. Harrist Jr.)。个人作品参加中国美术学院举办的当代书法展览《书非书》(2010年、2015年)。

她的博士论文《儒家精神与南朝风流的交会:北齐石刻书法传统的源流和传播(550-577)》,系统地梳理了北朝(以北齐为核心)书法传统源头与传播方式,考察了当时石刻书法的物质条件、制作与复制等问题。论文获得了瑞士苏黎世大学2015年秋季博士毕业论文最高荣誉(summa cum laude),由论文导师美国哥伦比亚大学韩文彬(Robert E. Harrist Jr.)教授推荐出版。该论文获中国美术学院视觉中国研究院赞助,列入“视觉中国论丛”(CIVS Series)系列,并由浙江人民美术出版社正式出版。

该书不仅获得了国家新闻出版总署重点推动的2018年度“经典中国国际出版工程”优秀图书出版项目资助,还获得了中国对外翻译与传播研究中心(CCTSS)颁发的国家丝路书香工程“外国人写作中国计划”荣誉证书,并纳入国家丝路书香工程“外国人写作中国计划”选题资料库。

My Calligraphic Adventure in Hangzhou

My Chinese name is You Li. I am from Zurich, Switzerland, but I often half-jokingly introduce myself as a Hangzhou native. I enjoy walking and cycling. I have my own leisurely, nostalgic way of enjoying Hangzhou, especially its lovely alleys. This is also the way I live my life and do my study. Over the years, I have changed a lot; but life itself does not change that much. Just like Kant, who never really left his hometown in his life but could still think big.

Calligraphy is like the music score, or a movement in some kind of dance. For me, it feels just beautiful. Every calligraphy copybook is like a dancer, who leaves marks through his/her own unique body language.

After receiving a scholarship from the University of Zurich in my third year at the Department of East-Asian Art History, I landed in Hangzhou in the summer of 1993 to further my study at China Art Academy. I still remember quite clearly my first day here: I got off the train and a pedicab took me to the campus. It was a breezy day and everything was beautiful.

I fell in love with inkslab and writing brushes on the day a Japanese teacher showed us Orchid Pavilion at a calligraphy class back in Zurich. In Hangzhou I showed up late for my first calligraphy class. Entering the classroom, I saw my teacher Li Wencai sit there and smoke a cigarette. I sat down in the first row, and the class began. Speaking Ningbo dialect and smoking throughout the class, Li started with the running script. I couldn’t understand a thing, and what he put down on the blackboard made no sense to me. I burst into tears, thinking about packing and going home.

I didn’t go home. Instead, I stayed for 10 years, and got a Master’s Degree from the academy in the end.

Back in those years, most international students at the academy dreamed of becoming an artist. However, I felt I was a blank piece of paper at that time. It is calligraphy that made me realize where I belonged. Back in the 1990s when the world was yet to be taken over by mobile phones, Nanshan Road was quiet and secluded, ideal for my daily ride on a Forever-brand bike to Park No.6 for my daily morning swordplay exercise. Classes were mostly in the morning; and I’d spend the afternoons and nights practicing calligraphy in the classroom. I never wasted a day. After I met Lu Dadong (my husband), calligraphy became not only my career, but also my faith and love.

I was never an obedient student. I spent all my free time in my second year of the undergraduate study in Hangzhou practicing calligraphy in Yan Zhenqing style, much against the will of my teacher. What some of the teachers told us also made me a little uneasy and doubtful. International students were told there was no need to actually visit the Stele Forest in Xi’an and that looking at the rubbings was enough to learn. There must be a lot of difference between writings on a piece of stone and that on a piece of paper, I wonder.

The core character of my doctoral dissertation is An Daoyi, a master monk and calligrapher living in the Northern Qi Dynasty (550-577). In fact, An Daoyi is the common thread that ran throughout my calligraphy exploration over the years. My husband and I followed the man’s footprints in multiple field trips that produced ample firsthand materials for the writing of my master’s thesis. The thesis turned out to be more archaeological than calligraphic, which made me rethink about my analytical capability.

My doctoral study began in the spring of 2004. The year turned out to be the start of more academic freedom as well as difficulty, partly because I found myself pregnant and later gave birth to my first child. After my teacher, Helmut Brinker, passed away in 2012, I became a student of Robert E. Harrist Jr., whose strict instruction helped me clear up my mind regarding the core ideas and research methodology of my doctoral dissertation. The oral defense at the University of Zurich went smoothly, but I needed to get my dissertation officially published before the doctorate could be granted, according to the requirement of the university. That’s how the book was born in Hangzhou.

Writing the dissertation and remaking it into something for publishing are two completely different things. It was almost rewriting, and it took four years of revising and solving all kinds of copyright issues regarding the use of pictures.

I want to take this opportunity to say thank you to many people who have supported me in the process, and my special thanks go to Gao Shiming, Wang Lianggui, Zhou Jing, Anne McGannon (the English editor of the book), Zhang Midi and Tao Junxia representing Yu Shu Tang, Wang Xiongwei and Luo Shitong from Zhejiang People’s Fine Arts Publishing House.

I also plan to work out a Chinese version of the book so that I can share with more people my understanding of Chinese calligraphy. One of our plans is an exhibition of all the rubbings and books, purchased and painstakingly collected by my husband to facilitate my research and writing over the years. The exhibits will also include many of my practice works during my undergraduate and postgraduate years in Hangzhou, which show a foreigner’s passion in and respect for Chinese calligraphic art.