海上丝绸之路,作为世界上最古老的海上航线之一,自古便是国际贸易和文化交往的海上交通动脉。中国通过海上丝绸之路往外输出的商品主要有丝绸、瓷器、茶叶和铜铁器四大宗,对内输入的主要是香料、花草及一些供宫廷赏玩的奇珍异宝。

16世纪初,葡萄牙人绕过非洲好望角,开辟了东方航线,中国与欧洲从此开始了直接的贸易往来。各国商人、传教士、旅行家来到中国,中国生丝与绸缎大量销往欧洲与美洲。

之后,西班牙、荷兰、英国、法国、德国、瑞典与丹麦等欧洲国家纷纷来华,在广州港进行季节性大采购,将中国的各种商品大量运往欧洲。

在繁忙的国际贸易中,丝绸在中国外销商品中占有很大比重。欧洲人在向中国大量订购丝绸的同时,也提供花样样本,希望按欧洲流行的风格样式制作。为适销对路,中国丝绸商人或按提供的来样加工,或尽可能模仿欧洲流行的洛可可风格,以满足欧洲人对中国风情的想象和理解。因此,人们说到外销绸(Export silk),其概念却是十分清楚,专指18世纪、19世纪前后,中国为外销设计、生产,并输出到世界各地特别是欧美各国的丝绸织绣品。

英国版画家眼中的丝绸制作

外销绸精品主要包括外销绢画、外销织物、手绘外销绸、外销服饰、外销家纺等。

外销绢画兴盛于18世纪、19世纪。中国画师为迎合西方社会热衷“中国趣味”的风尚,采用西洋绘画的技法(包括透视法、色彩晕染)、形式和材料,绘制带有中国风情的图画。这些绢画通常是销往欧洲,后也及于美国。外销绢画既有别于传统的中国画,又不同于地道的西洋画,西方人买回家通常直接贴在墙上,不作卷轴或镜框装裱。

从内容看,多表现中国式生产和生活的场景,特别是富裕家庭快乐闲适的生活。另外,表现农民和城市手工业者的生产活动的作品也比较常见,如耕织、采茶、养蚕,及家具、瓷器生产。

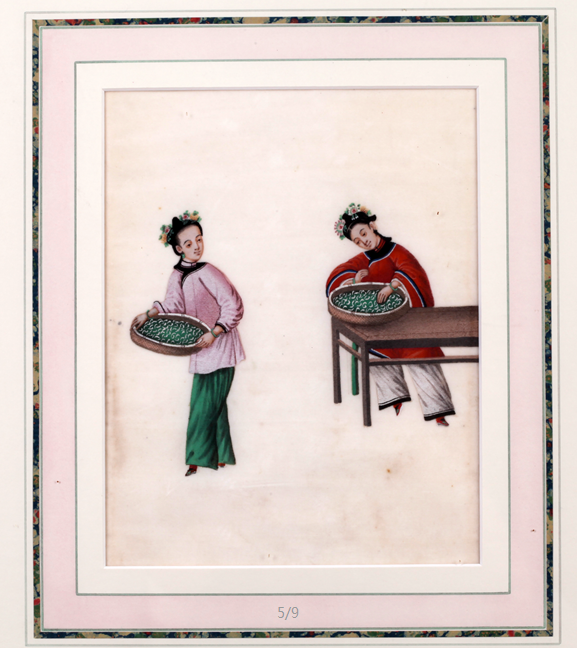

外销绢画《养蚕》和《选茧》,再现了养蚕、选蚕的生产情景。画中的妇女虽然是在从事养蚕的农活,但柳叶眉、樱桃小嘴、窄溜肩,配上华贵的发饰和服装,显然不是真正的蚕妇。在画法上,画家融合了西洋画法,对人物脸部、手部、躯干、衣褶和头饰等部位进行细腻描绘,产生的效果与20世纪初上海流行的月份牌画相似,透露出浓厚的东方情调。

托马斯·阿洛姆(Thomas Allom,1804~1872),是英国皇家建筑师协会创建人、版画家。中国之行让阿洛姆发现了宝库,他亢奋不已,创作的佳作无数。回国后,便出版了《中国:那个古代帝国的风景、建筑和社会习俗》。钢版画《煮茧与缫丝》和《染坊》,就是阿洛姆的作品,虽然不是一般意义上的外销绢画,但是同样不失那一时期中西合璧的艺术品所具有的特征。

《煮茧与缫丝》中西结合,别有意趣。画中飞檐宝塔,场景是典型的中国风格,而人物形象是高鼻深目的西洋人士。《染坊》画面呈“Z”字形构图,用水塘分割、连接前后建筑物,绿树碧波与飞檐红瓦相映成趣。画中反映了染色的主要工艺流程,四只大染缸一目了然,上下晾挂各色染好的织物,准确地交代了染坊场景。正在劳动的人物,位于画面前部的男人或搅或漂或绞或晾,位于后部的女人六人三组正在裁卷白色的匹料,人物姿态丰富,生动图解了染坊的工艺流程。人物表情刻画细腻,从发髻和服饰来看是中国样式,但是面部高鼻深目,又是十分典型的西洋人。

千里迢迢,从江浙运到广州

当时的欧洲国家大量进口中国丝绸,用于家居装饰和服装面料,其中相当一部分织物保存至今。这些织物主要用于室内装饰,如墙面及沙发、椅子等,鹅黄、大红、深绿是最常见的颜色。在花纹装饰上,花型大,对称连续,色彩十分艳丽。

蕾丝是欧洲17世纪至18世纪初流行的设计元素。维多利亚时代,女人们喜欢在领口、袖口、裙摆处露出内衣的蕾丝花边,而就算是当时流行的下午茶,也要铺上白色刺绣蕾丝的桌布和餐巾,才显得情调十足。拖曳的蕾丝、缎带纹样是18世纪60年代欧洲丝绸设计中的流行纹样,外销织物把蕾丝作为纹样,充分关照了欧洲当时的流行时尚。

由于提花织物的生产需要织机重新装造,费时费工,且高质量的提花锦缎来自江南,远途运输不便。在清乾隆仅留粤海关一口对外通商时,外销货物需汇聚广州,其中最为重要的路线是陆路:先自苏州、湖州等丝绸产地集中起来运往杭州,再逆富春江船运而上,到浙、赣边界的常山县卸船挑运,翻山挑至江西省的玉山县再装船,顺信江而下,达河口镇,从河口镇运至都阳湖,然后转入赣江,逆流而上到赣州的大庚县起岸,越梅岭穿梅关到广东南雄州的始兴县,第三次装船运至韶州,最后顺北江运至广州。

江浙丝绸也曾走过海路,有史料提到,一些商人经营江浙一带生产的辑里丝,“冒险航海至广州,经公行之手与英商交易”。这条路线虽比陆路更为便利,只是明清之际海禁森严,作用发挥有限。

中国丝绸在进入欧洲后,受到热烈欢迎。有一部分外销绸直接制作成服装出口,当时欧洲和美洲的相当一部分宗教服饰即来自中国。在法国,刺绣服装更是受宠,从绅士的西式背心到贵妇们的鞋面都用丝绸织锦做面料,并饰以刺绣图案。

同时,也有一些中式丝绸服饰虽不是作为外销品设计制作,但是,这些服饰以其绚丽华美和有别于欧美时装的宽松形制,成为西方中上层女性喜爱的室内着装,常用于晨衣及下午茶装束。美国画家Arvid Frederick Nyholm(1866-1927)画于20世纪20年代的《穿着物的年轻女子》(Young Woman in Kimono)中,一位穿着类似中式女褂的西方女子正优雅地倚在瓶花边,陷入绮思。领口的英文商标表明它曾在位于纽约第五大道专营东方珍奇的Vantine’s外贸店销售。Vantine’s由Ashley Abraham Vantine (1828—1890) 于1866年在纽约成立,主要经营物美价廉的各色中、日摆设和服饰,原店位于百老汇大街,1913年后迁移至第五大道436号。1921年该店短暂关闭之后,于1923年重新开张,直至1930年破产。这件衣服上的商标是该店1923~1930年间所使用的设计。

执扇和撑阳伞的女性形象

18世纪至19世纪,中国的外销扇也同样风靡欧美,身着华丽晚礼服的贵妇,竞相以手执一柄小巧精致、具有东方情趣的扇子为时尚。这些专供外销的扇子和中国传统的扇子有明显的区别——色彩艳丽、纹饰华美、材质多样。擅长描绘室外场景和光影变幻的法国印象派画家,捕捉了许多各种场合执扇和撑阳伞的女性形象,从画中人物的扇子、阳伞等细节,可以看出中国外销配饰已经成为当时法国时尚生活的一个部分。安格尔、莫里索、雷诺阿、马奈、莫奈等著名印象派画家都曾画过这类作品,或在包厢,或在花园,或在阳台,或执扇,或撑伞……浪漫优雅的女性更显动人。

19世纪中期,随着欧洲公共花园的兴起,中上层女性的户外活动增多。在伦敦、巴黎等大都市,到公园散步、野餐等,成为女性日常休闲活动的一部分,外出服饰亦随之成为时尚展示的重要一环。太阳伞是女性外出必备的配饰,有些伞面会绣上传统的吉祥图案,有趣的动物、植物,历史传说中的英雄好汉以及戏曲和神话故事,反映中国式的思想情感与善恶判断,具有深刻的文化内涵。

戏曲故事和戏曲人物是中国刺绣中常见的题材,人们将戏曲中的人物与场景,经过巧妙的艺术处理,创作成不同样式的刺绣作品,这一幅幅刺绣就如同一出出凝固的戏剧,抒发了人们情感。这些美丽的故事随着中外文化的交流,在欧洲的一些戏剧和小说中,以中国式的情节,准确地说是异国情调的中国样式出现,受到热烈的欢迎。“中国戏”和“中国小说”于是成为欧洲“中国热”中的一道景观,这也反映在与当时时尚生活紧密联系的阳伞上。如雷诺阿作于1867年的《撑伞的女人》,画中站在树边的女子手持的就是黑色蕾丝太阳伞。

18世纪、19世纪的欧洲国家从中国进口丝绸,除了用于服饰,还大量用于室内装饰。尤其是宫殿,床罩、帷幔和窗帘都采用丝绸,甚至家具也配有丝绸刺绣的外罩,如桌布、坐垫等。这些室内装饰品,以缎地广绣为大宗,普遍采用广绣形式,色泽丰富,布局饱满,繁而不乱。题材多以百鸟朝凤、杏林春燕、锦鸡牡丹、龙凤呈祥等吉祥事物为题材,少有空隙,即使有空隙也要用山水草地树根等补充,用以表现吉祥富贵、喜庆满堂、生机勃勃的寓意。

外销绸进入欧洲,受到消费者的欢迎,风靡一时的中国风尚体现在当时整个欧洲社会中,并渗透到欧洲人生活的各个层面。但是,与别的中国丝绸收藏不同,外销绸的收藏大多是在国外。广东省博物馆等博物馆经过多年努力,有了一定的藏品积累,但是无论数量、种类,都远远没有达到可资全面、深入研究和展示的程度。

A Silky Tale

A Glimpse into China’s History of Silk Export

One of the world’s most ancient sea routes, “Silk Road on the Sea” once served as a trade and cultural communicating artery, with silk being a compelling evidence of this ancient ocean trade route between China and Europe - from Guangzhou and Quanzhou in the southeast of China to West Asia, North Africa, and East Africa.

For a prolonged period of time throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, silk merchants in China received considerable orders from Europeans who provided design samples of rococo styles.

Silk products from China included Chinese paintings on silk, selected fabrics, hand-drawn silk, ready-to-wear garments, and silk home textile items. Chinese paintings on silk, using traditional Chinese themes such as family happiness, picking tea-leaves and silkworm breeding and Western painting techniques such as polishing and perspective, were much sought-after in Europe and America in the 18th and 19th centuries. The paintings were loved for their Western-style approach to details as well as their strong Oriental sentiments.

Thomas Allom (1804-1872), an English architect, artist, and topographical illustrator, described his China adventure as discovering a treasure trove. After returning to England, he created a lot of works drawing inspiration from the Oriental kingdom and published a book about the scenic, cultural and architectural magnificence of China. In one of his paintings, traditional Chinese silkworm breeding and silk reeling is put together with fair-skinned, high-bridged Caucasians.

Lace became a popular fashion element across Europe during the 17th and early 18th centuries, finding its way into the wardrobe of upper-class women of the Victorian age. The lace patterns prevailing in the silk pieces exported from China to Europe in the 1760s demonstrate the business acumen of Chinese exporters at that time.

Historical documents show the more daring silk merchants risked their life to send the high-quality jacquard fabrics from China’s Jiangnan regions, especially the silk pieces from Jili in present-day Huzhou in Zhejiang Province, to dealers in Guangzhou via sea routes, at a time when maritime trade was totally banned by the Qing government.

Silk from China was in hot demand in Europe. Some of the exported silk was made into ready-to-wear clothes, many of which fell into the religious clothing category, before entering Europe. Embroidered fabric from China became a new fashion trend among the more privileged people in France.

Even Chinese-style silk garments that were not originally designed for Westerners were much sought-after. Upper-class ladies scrambled to buy baggy, lavishly decorated and glossy pieces to use as morning wear or afternoon tea fashion, as can be seen in, created by American artist Arvid Frederick Nyholm (1866-1927) in the 1920s. In the art piece, the collar and shows the Chinese-style silk robe worn by the lady leaning against a beautiful vase was purchased from Vantine’s, a boutique place located on Fifth Avenue in New York. Founded in 1866 by Ashley Abraham Vantine (1828—1890), the fashion shop enjoyed a hard-core fan base for its affordable, selected collection of the Oriental fashion rarities, mostly from China and Japan.

Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, high quality exported fans from China was also part of the standard fashion configuration of ladies from the high society of Europe. Chinese-style fans and parasols decorated with traditional Chinese patterns drawing inspiration from myths, folktales and Chinese operas added a lot of flair and romance to the grace of the women portrayed by the most renowned impressionists such as Pierre-August Renoir, Édouard Manet and Claude Monet. It is no exaggeration to say that silk fashion triggered a “China fever” among upper-class Europeans.

Chinese silk exported to European countries was also widely used for interior decoration, made into bedspreads, draperies, curtains, tablecloths and even furniture covers. The auspicious themes conveyed by the embroidered patterns on the fabric, such as dragon and phoenix, peony blossoms and golden pheasants, were well-received all over the European market.

In a sense, exported silk not only beautified the life and art of the Europeans but also brought the multifaceted Chinese culture into their daily lives. It is a pity that we are far from being able to conduct in-depth research in this exciting chapter of China’s foreign trade history, due to a serious lack of exported silk collection in China. The Guangdong Museum in China has a collection of silk products domestically made in ancient times for international markets, but the collection is by no means good enough in both quality and quantity to support any in-depth study.